http://www.asyura2.com/12/hasan76/msg/428.html

| Tweet |

http://ikedanobuo.livedoor.biz/archives/51792802.html

2012年06月03日 15:04 テクニカル

財政赤字で景気は悪くなる

私にスパムを飛ばしてくる匿名アカウントの共通点は「反原発・反消費税・反TPP」だ。この3つには共通点がある。長期のコストを無視して短期の利益を最大化するということだ。アゴラにも書いたことだが、これはこれで一つの考え方である。

http://agora-web.jp/archives/1459490.html

いま日本で起こっている政治的対立も、「保守vsリベラル」とか「小さな政府vs大きな政府」というより、長期vs短期の対立と考えたほうがわかりやすい。これは経済学でいうと、時間選好率の違いである。現在(1)と将来(2)の2期モデルで考え、現在の消費をC1、将来の消費をC2、時間選好率をRとすると、消費の割引現在価値Vは新古典派理論では

V=C1+C2/(1+R)・・・(1)

と表わされる。金利をIとすると、視野が長期的で将来の消費の価値を金利で割り引く場合にはR=Iだから、きょうの消費とあすの消費の価値は同じで、課税のタイミングの変化は消費に影響を及ぼさない。これがリカードの中立命題(等価定理)である。

他方、視野が短期的でR>Iだとすると、課税を延期する(国債を発行する)ことによって消費は増える。現実には中立命題は成り立たないので、時間選好率は金利よりかなり高いと考えられる。極端な場合として(1)式でR=∞とすると

V=C1・・・(2)

となり、国債の発行で現在の所得が増えれば消費が増え、将来の増税は現在の消費に影響を及ぼさない。これがケインズの「限界消費性向」の理論である。時間選好率についてはいろいろな推定があるが、上の2つの式で明らかなのは、ケインズ理論は新古典派の特殊な場合だということだ。ケインズが『一般理論』を「古典派」の一般化だと称したのは逆なのである。

将来は死んでいる老人にとっては、いま借金してすべて消費することが合理的だから、(2)式の「どマクロ」理論が妥当する。しかし将来も生きている現役世代は、財政赤字が増えると(1)式のC2/(1+R)が減るので、現在の消費を減らして老後にそなえるだろう。そういう現象が消費の低迷の原因になっていると思われる。

http://ikedanobuo.livedoor.biz/archives/51791730.html

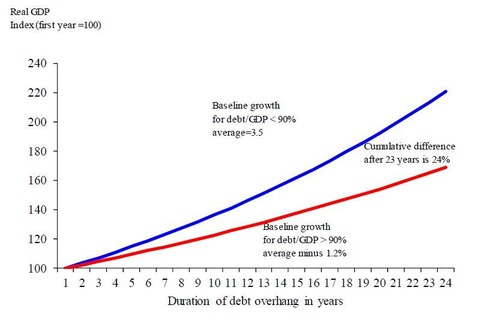

こういう傾向は、実証的にも確認されている。ロゴフは、過去の財政危機のデータから政府債務がGDPの90%を超えた国では成長率が1.2%ポイント下がるという法則を見出している。この結果、図のように23年間に24%もGDPが低下する。その典型が日本である。つまり「増税で景気が悪くなる」というのは逆で、財政赤字で景気は悪くなる。「景気か財政再建か」というトレードオフはないのである。

「テクニカル」カテゴリの最新記事

財政赤字で景気は悪くなる

ICRPの線量基準は1000倍以上の過大評価

なぜ「地元の民意」を問うべきではないか

クルーグマンの量的緩和論

Voiceからexitへ

代表性の神話

東電のスマートメーター「国際入札」は延期して見直せ

既得権保護の合理性

サンクコストと資本主義

スマートメーターのゼネコン構造

青木 隆志 · トップコメント投稿者 · 自営業(個人事業主) 代表

記事に上げる短期の利益しか見ない人間の他にもう1つの人種がいる。「革命的祖国敗北主義」を狙う人間。ロシアも日本も戦争に負けたおかげで旧態依然とした体制が駆逐されて、見事な発展を見せた。リフレ論は金融テロ、反原発も産業テロなんで諸手を上げて賛成することはできないが、僕はまだ若く能力もあるので歴史の濁流に立ち向かえる。ただ、親たちと思うと伏目がちにならざるをえないが・・・。

返信 · 1 · · 8時間前

すずき あきら · 勤務先: 日本

増税による財政改革で景気が良くなるとした前の記事と合わせて読むと分り易いですね。

ただ増税だけではダメだと思います。一緒に生産性を向上させる施策が必須でしょう。民間の生産性向上に政府が介入するのは難しいですが、公共部門の生産性向上は直ぐ可能でしょう。マクロ経済学者として公共部門がどの程度足を引っ張っているのか?あるいは本当は引っ張っていないのか?解説した記事があると良いと思います。

返信 · · 5時間前

Tetsuharu Kawasaki · トップコメント投稿者 · 石川工業高等専門学校

池田氏は管首相の時代から『TPP推進』を謳っております。また福島原発事故の対応について『管首相&内閣中枢には大きな欠陥がある』旨の発言もしています。

この2つを合わせて考えると『TPP交渉は無能でも上手いこと交渉できる』と認識されていると解釈できます。

そんなに甘いものなんですかね??

返信 · · 4時間前

冨田 賀彦 · 早稲田大学

>政府債務がGDPの90%を超えた国では成長率が1.2%ポイント下がる

簡単に考えて、

1)外国からの投資が減る

2)年金などの社会保障制度に不安を持ち、消費を控える

3)公共投資が抑制される

などが生じるとおもいます。

増税でこれらを解消することで、成長路線に乗せる。

正論だと思います。

返信 · · 6時間前

舛元伸一 · 株式会社リョーイン 執行役員 広島営業所 所長

分かりやすい。

返信 · · 約1時間前

http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/austerity-and-debt-realism

Austerity and Debt Realism

CommentsCAMBRIDGE – Many, if not all, of the world’s most pressing macroeconomic problems relate to the massive overhang of all forms of debt. In Europe, a toxic combination of public, bank, and external debt in the periphery threatens to unhinge the eurozone. Across the Atlantic, a standoff between the Democrats, the Tea Party, and old-school Republicans has produced extraordinary uncertainty about how the United States will close its 8%-of-GDP government deficit over the long term. Japan, meanwhile is running a 10%-of-GDP budget deficit, even as growing cohorts of new retirees turn from buying Japanese bonds to selling them.

Illustration by Jim Meehan

CommentsAside from wringing their hands, what should governments be doing? One extreme is the simplistic Keynesian remedy that assumes that government deficits don’t matter when the economy is in deep recession; indeed, the bigger the better. At the opposite extreme are the debt-ceiling absolutists who want governments to start balancing their budgets tomorrow (if not yesterday). Both are dangerously facile.

CommentsThe debt-ceiling absolutists grossly underestimate the massive adjustment costs of a self-imposed “sudden stop” in debt finance. Such costs are precisely why impecunious countries such as Greece face massive social and economic displacement when financial markets lose confidence and capital flows suddenly dry up.

CommentsOf course, there is an appealing logic to saying that governments should have to balance their budgets just like the rest of us; unfortunately, it is not so simple. Governments typically have myriad ongoing expenditure commitments related to basic services such as national defense, infrastructure projects, education, and health care, not to mention to retirees. No government can just walk away from these responsibilities overnight.

CommentsWhen US President Ronald Reagan took office on January 20, 1981, he retroactively rescinded all civil-service job offers extended by the government during the two and a half months between his election and the inauguration. The signal that he intended to slow down government spending was a powerful one, but the immediate effect on the budget was negligible. Of course, a government can also close a budget gap by raising taxes, but any sudden shift can significantly magnify the distortions that taxes cause.

CommentsIf the debt-ceiling absolutists are naïve, so, too, are simplistic Keynesians. They see lingering post-financial-crisis unemployment as a compelling justification for much more aggressive fiscal expansion, even in countries already running massive deficits, such as the US and the United Kingdom. People who disagree with them are said to favor “austerity” at a time when hyper-low interest rates mean that governments can borrow for almost nothing.

CommentsBut who is being naïve? It is quite right to argue that governments should aim only to balance their budgets over the business cycle, running surpluses during booms and deficits when economic activity is weak. But it is wrong to think that massive accumulation of debt is a free lunch.

CommentsIn a series of academic papers with Carmen Reinhart – including, most recently, joint work with Vincent Reinhart (“Debt Overhangs: Past and Present”) – we find that very high debt levels of 90% of GDP are a long-term secular drag on economic growth that often lasts for two decades or more. The cumulative costs can be stunning. The average high-debt episodes since 1800 last 23 years and are associated with a growth rate more than one percentage point below the rate typical for periods of lower debt levels. That is, after a quarter-century of high debt, income can be 25% lower than it would have been at normal growth rates.

CommentsOf course, there is two-way feedback between debt and growth, but normal recessions last only a year and cannot explain a two-decade period of malaise. The drag on growth is more likely to come from the eventual need for the government to raise taxes, as well as from lower investment spending. So, yes, government spending provides a short-term boost, but there is a trade-off with long-run secular decline.

CommentsIt is sobering to note that almost half of high-debt episodes since 1800 are associated with low or normal real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates. Japan’s slow growth and low interest rates over the past two decades are emblematic. Moreover, carrying a huge debt burden runs the risk that global interest rates will rise in the future, even absent a Greek-style meltdown. This is particularly the case today, when, after sustained massive “quantitative easing” by major central banks, many governments have exceptionally short maturity structures for their debt. Thus, they run the risk that a spike in interest rates would feed back relatively quickly into higher borrowing costs.

CommentsWith many of today’s advanced economies near or approaching the 90%-of-GDP level that loosely marks high-debt periods, expanding today’s already large deficits is a risky proposition, not the cost-free strategy that simplistic Keynesians advocate. I will focus in the coming months on the related problems of high private debt and external debts, and I will also return to the theme of why this is a time when elevated inflation is not so naïve. Above all, voters and politicians must beware of seductively simple approaches to today’s debt problems.

Reprinting material from this Web site without written consent from Project Syndicate is a violation of international copyright law. To secure permission, please contact us.

|

|

|

|

この記事を読んだ人はこんな記事も読んでいます(表示まで20秒程度時間がかかります。)

|

|

スパムメールの中から見つけ出すためにメールのタイトルには必ず「阿修羅さんへ」と記述してください。

スパムメールの中から見つけ出すためにメールのタイトルには必ず「阿修羅さんへ」と記述してください。すべてのページの引用、転載、リンクを許可します。確認メールは不要です。引用元リンクを表示してください。