http://www.asyura2.com/12/genpatu23/msg/859.html

| Tweet |

#広島・長崎の被爆者12万人の追跡期間を6年延長した結果、全線量で余剰癌死亡率(ERR)が上がり、特に500mSv(0.5Gy)以下では線形関係を上回るデータだが、

相変わらず池田信夫は強気だ(1Sv/年程度なら5%程度の発がんリスクの上昇=運動不足や塩分過剰以下のリスク)

http://blogos.com/article/39485/

年間1Sv被曝しても健康被害は出ない

池田信夫

2012年05月21日 13:55

•

今週のGEPRでは、ちょっとおもしろいデータを紹介している。

まず放射線影響研究所の最新レポート。これは広島・長崎の被爆者12万人を追跡調査している、世界でもっとも権威ある放射線の影響についてのレポートだ。今回は今までに比べて全線量で余剰癌死亡率(ERR)が上がり、特に500mSv(0.5Gy)以下では線形関係を上回るデータが出ている(有意性は低い)。

この解釈はむずかしいところで、英語の原論文でも明快な結論を出していないが、もっとも自然な説明はホルミシス効果だろう。今までの研究では500mSvぐらいまでは放射線量を増やすと発癌率が減少するというデータが得られているので、上の図とほぼ整合的だ。放影研も「低線量の関係は線形というより凹型」だとしている。

いずれにせよ、このデータで確実にいえるのは、瞬間100mSv以下の被曝による余剰癌死亡率は5%以下だということである。このリスクは受動喫煙や野菜不足とほぼ同じで、塩分の取りすぎや運動不足より小さい。

しかもこのリスクは瞬間被曝によるもので、持続的な被曝のリスクはよくわかっていない。これについても今週のGEPRでMITのレポートを紹介している。それによると、マウスのDNAに放射線を照射した実験では、毎時120μSv(年間1.05Sv)を5週間にわたって照射しても、DNAの切断は見られなかった。

この数値がICRPの定める年間線量に対応する。現在の基準は「平時」で年間1mSvだが、MITの実験ではこの数値の1050倍でも遺伝子に影響は出ていない。どれぐらいの被曝量で影響が出るのかは未知だが、年間260mSvのラムサールでも影響は出ていない。サンプルは少ないが、時計職人で累計10Svで影響が出たというデータがある。

だから科学的にいえることは、保守的に見積もってもICRP基準の1000倍の被曝でも健康被害は出ないということである。年間1Sv(毎時120μSv)という線量は福島県の平均線量の100倍以上なので、今回の事故の放射線による発癌リスクはまったくないと断定してよい。瞬間100mSv被曝すると受動喫煙ぐらいのリスクがあるが、同量の持続的照射の影響はそれよりはるかに低い。

低線量被曝についてはGEPRで多くのデータを公開しているが、世界の科学的研究の結論はほぼ一致している。科学的な批判は歓迎する。

追記:ERRの桁を間違えていた。失礼。

この記事を筆者のブログで読む

https://qir.kyushu-u.ac.jp/dspace/bitstream/2324/20570/1/full-33-3-2.pdf

低線量放射線被曝によるがん発生に関する元データーの 誤差論

LNT仮説は0.1Gy以下まで十分精度がある

3. 結言

以上,RERFによる原爆被曝者のLSSから求められた被曝量と固形がん発症率あるいは白血病死亡率調査を誤差論に基づいて再吟味したところ、以下の結論を得た.

1.

もとの RERF 要覧では被曝吸収線量と固形がん発症率あるいは白血病死亡率を男女別あるいは被曝年齢別に分け、調査報告している。第一義的に重要な事は、人が放射線によりどのような率でがん発症あるいは死亡するかを見極めることである。

例えば、男女間で若干の差が見られても、男女のがん発症率で合計して見て、データー精度を高めプロットすると、より精度高く評価できる事が分かった.

2.

母集団が二項分布あるいはポアソン分布に従うとして、誤差を評価したところ、固形がん発症率と原爆被曝線量での直線関係は、0.1Gy 以下まで十分な精度があり、LNT 仮説が適用できる事が認められた.白血病でも、0.1Gy 程度まで死亡率と原

爆被曝量との間に線形の相関が見られる事が分かった.

3.

相対リスクは、被曝量0で1に収束し、定性的なガンリスクを理解しやすいが、余剰リスクは定量的なリスクに適しており、被曝量とガンリスクの関係をより明らかに見ることができる。

http://hiwihhi.com/ikedanob/status/204409731887005697

原爆被爆者の死亡率に関する研究、第14 報、1950−2003、がんおよび非がん疾患の概要

http://www.rerf.or.jp/news/pdf/lss14.pdf

器疾患、呼吸器疾患、消化器疾患でのリスクが増加したが、放射線と

の因果関係については更なる検討を要する。

【解説】

1) 本報告は、2003 年のLSS 第13 報より追跡期間が6 年間延長された。DS02 に基づ

く個人線量を使用して死因別の放射線リスクを総括的に解析した初めての報告である。

解析対象としたのは、寿命調査集団約12 万人のうち直接被爆者で個人線量の推定され

ている86,611 人である。追跡期間中に50,620 人(58%)が死亡し、そのうち総固形が

ん死亡は10,929 人であった。

2) 30 歳被曝70 歳時の過剰相対リスクは0.42/Gy(95%信頼区間: 0.32, 0.53)、過剰絶

対リスクは1 万人年当たり26.4 人/Gy であった。

*過剰相対リスクとは、相対リスク(被曝していない場合に比べて、被曝している場合のリスクが何倍になってい

るかを表す)から1 を差し引いた数値に等しく、被曝による相対的なリスクの増加分を表す。

*過剰絶対リスクとは、ここでは、被曝した場合の死亡率から被曝していない場合の死亡率を差し引いた数値で、

被曝による絶対的なリスクの増加分を表す。

3) 放射線被曝に関連して増加したと思われるがんは、2 Gy 以上の被曝では総固形が

ん死亡の約半数以上、0.5−1 Gy では約1/4、0.1−0.2 Gy では約1/20 と推定された。

4) 過剰相対リスクに関する線量反応関係は全線量域では直線であったが、2 Gy 未満

に限ると凹型の曲線が最もよく適合した。これは、0.5 Gy 付近のリスク推定値が直線モ

デルより低いためであった。

放射線影響研究所は、広島・長崎の原爆被爆者を 60 年以上にわたり調査してきた。その研

究成果は、国連原子放射線影響科学委員会(UNSCEAR)の放射線リスク評価や国際放射線

防護委員会(ICRP)の放射線防護基準に関する勧告の主要な科学的根拠とされている。

Radiation Research 誌は、米国放射線影響学会の公式月刊学術誌であり、物理学、化学、生

物学、および医学の領域における放射線影響および関連する課題の原著および総説を掲載し

ている。(2010 年のインパクト・ファクター: 2.578 )

被爆時年齢および到達年齢が総固形がん死亡の放射線リスクに与える修飾効果

ERR/Gy:1Gy 被曝した場合の過剰相対リスク

EAR/104person-year/Gy: 1Gy 被曝した場合の過剰絶対リスク(10,000 人あたりの増加数)

・ 被爆時年齢が若い人ほどリスクが大きい(10 歳若いとERR が約30%増加)

・ 被爆後年数がたつほど(本人が高齢になるほど)、相対的なリスクは小さくなる(10 歳の加齢でERR が

10〜15%の減少)

・ 一方、本人が高齢になるほど、がんによる死亡率は大きくなるので、過剰ながん死亡(EAR)は多くなる

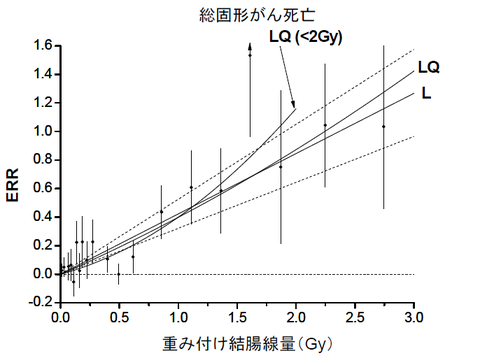

図4.総固形がん死亡に対する放射線による過剰相対リスク(ERR)の線量反応関係

ERR の線量反応関係は全線量域では直線モデル(L)が最もよく適合したが、2Gy 未満に限ると線形二次

モデル(LQ)が最もよく適合した。これは、0.5Gy 付近のリスク推定値が直線モデルより低いためであった。

図中の点と縦線は線量カテゴリーごとの点推定値と95%信頼区間である。点線は、全線量域で最適であっ

た線型モデル(L)の95%信頼区間である。

http://web.mit.edu/newsoffice/2012/prolonged-radiation-exposure-0515.html

A new look at prolonged radiation exposure

MIT study suggests that at low dose-rate, radiation poses little risk to DNA.

Anne Trafton, MIT News Office

May 15, 2012

A new study from MIT scientists suggests that the guidelines governments use to determine when to evacuate people following a nuclear accident may be too conservative.

The study, led by Bevin Engelward and Jacquelyn Yanch and published in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives, found that when mice were exposed to radiation doses about 400 times greater than background levels for five weeks, no DNA damage could be detected.

Current U.S. regulations require that residents of any area that reaches radiation levels eight times higher than background should be evacuated. However, the financial and emotional cost of such relocation may not be worthwhile, the researchers say.

“There are no data that say that’s a dangerous level,” says Yanch, a senior lecturer in MIT’s Department of Nuclear Science and Engineering. “This paper shows that you could go 400 times higher than average background levels and you’re still not detecting genetic damage. It could potentially have a big impact on tens if not hundreds of thousands of people in the vicinity of a nuclear powerplant accident or a nuclear bomb detonation, if we figure out just when we should evacuate and when it’s OK to stay where we are.”

Until now, very few studies have measured the effects of low doses of radiation delivered over a long period of time. This study is the first to measure the genetic damage seen at a level as low as 400 times background (0.0002 centigray per minute, or 105 cGy in a year〜1.05Sv/y=0.12Sv/h).

“Almost all radiation studies are done with one quick hit of radiation. That would cause a totally different biological outcome compared to long-term conditions,” says Engelward, an associate professor of biological engineering at MIT.

How much is too much?

Background radiation comes from cosmic radiation and natural radioactive isotopes in the environment. These sources add up to about 0.3 cGy per year per person, on average.

“Exposure to low-dose-rate radiation is natural, and some people may even say essential for life. The question is, how high does the rate need to get before we need to worry about ill effects on our health?” Yanch says.

Previous studies have shown that a radiation level of 10.5 cGy, the total dose used in this study, does produce DNA damage if given all at once. However, for this study, the researchers spread the dose out over five weeks, using radioactive iodine as a source. The radiation emitted by the radioactive iodine is similar to that emitted by the damaged Fukushima reactor in Japan.

At the end of five weeks, the researchers tested for several types of DNA damage, using the most sensitive techniques available. Those types of damage fall into two major classes: base lesions, in which the structure of the DNA base (nucleotide) is altered, and breaks in the DNA strand. They found no significant increases in either type.

DNA damage occurs spontaneously even at background radiation levels, conservatively at a rate of about 10,000 changes per cell per day. Most of that damage is fixed by DNA repair systems within each cell. The researchers estimate that the amount of radiation used in this study produces an additional dozen lesions per cell per day, all of which appear to have been repaired.

Though the study ended after five weeks, Engelward believes the results would be the same for longer exposures. “My take on this is that this amount of radiation is not creating very many lesions to begin with, and you already have good DNA repair systems. My guess is that you could probably leave the mice there indefinitely and the damage wouldn’t be significant,” she says.

Doug Boreham, a professor of medical physics and applied radiation sciences at McMaster University, says the study adds to growing evidence that low doses of radiation are not as harmful as people often fear.

“Now, it’s believed that all radiation is bad for you, and any time you get a little bit of radiation, it adds up and your risk of cancer goes up,” says Boreham, who was not involved in this study. “There’s now evidence building that that is not the case.”

Conservative estimates

Most of the radiation studies on which evacuation guidelines have been based were originally done to establish safe levels for radiation in the workplace, Yanch says ― meaning they are very conservative. In workplace cases, this makes sense because the employer can pay for shielding for all of their employees at once, which lowers the cost, she says.

However, “when you’ve got a contaminated environment, then the source is no longer controlled, and every citizen has to pay for their own dose avoidance,” Yanch says. “They have to leave their home or their community, maybe even forever. They often lose their jobs, like you saw in Fukushima. And there you really want to call into question how conservative in your analysis of the radiation effect you want to be. Instead of being conservative, it makes more sense to look at a best estimate of how hazardous radiation really is.”

Those conservative estimates are based on acute radiation exposures, and then extrapolating what might happen at lower doses and lower dose-rates, Engelward says. “Basically you’re using a data set collected based on an acute high dose exposure to make predictions about what’s happening at very low doses over a long period of time, and you don’t really have any direct data. It’s guesswork,” she says. “People argue constantly about how to predict what is happening at lower doses and lower dose-rates.”

However, the researchers say that more studies are needed before evacuation guidelines can be revised.

“Clearly these studies had to be done in animals rather than people, but many studies show that mice and humans share similar responses to radiation. This work therefore provides a framework for additional research and careful evaluation of our current guidelines,” Engelward says.

“It is interesting that, despite the evacuation of roughly 100,000 residents, the Japanese government was criticized for not imposing evacuations for even more people. From our studies, we would predict that the population that was left behind would not show excess DNA damage ― this is something we can test using technologies recently developed in our laboratory,” she adds.

The first author on these studies is former MIT postdoc Werner Olipitz, and the work was done in collaboration with Department of Biological Engineering faculty Leona Samson and Peter Dedon. These studies were supported by the DOE and by MIT’s Center for Environmental Health Sciences.

Share on facebookShare on google_plusone

Share on stumbleuponShare on diggShare on redditShare on deliciousMore Sharing Services209

Share on email

Comments

Log in to write comments

johnwerneken 2012-05-18 05:55:18

The arguing I hear is mostly I the other direction: that large dose studies whether in the lab or facilitated by meltdowns or actual atomic explosions may understate what some epidemiologist types think they see as cumulative effects of multitudes of small doses.

Zod 2012-05-21 04:47:38

I've never once heard that put forward by a rational person or someone in the field. Although we're data starved, all evidence (like people who live in much higher background levels and studies like this) suggest that we overestimate low dose threats. I'm willing to guess that whoever was selling you that claim had an anti-nuclear agenda.

sugawara - Gave courage to Fukushima. 2012-05-21 04:52:32

Fukushima people are scared to radioactivity. However, the paper of MIT, gave courage to Fukushima.

|

|

|

|

この記事を読んだ人はこんな記事も読んでいます(表示まで20秒程度時間がかかります。)

▲このページのTOPへ ★阿修羅♪ > 原発・フッ素23掲示板

|

|

スパムメールの中から見つけ出すためにメールのタイトルには必ず「阿修羅さんへ」と記述してください。

スパムメールの中から見つけ出すためにメールのタイトルには必ず「阿修羅さんへ」と記述してください。すべてのページの引用、転載、リンクを許可します。確認メールは不要です。引用元リンクを表示してください。