| Tweet |

下記は読売ニュースからの転載であるが、其の下に、興味深い関連記事を紹介している。

http://www.yomiuri.co.jp/space/news/20090306-OYT1T00518.htm

「都市一つ壊滅したかも」小惑星あわや激突…豪学者が観測

【ブリスベーン=岡崎哲】3日未明、直径30〜50メートルの小惑星が地球の近くをかすめていたことが、オーストラリア国立大学の天文学者、ロバート・マクノート博士の観測で分かった。

最接近時には地球からわずか約6万キロの距離で、博士は「衝突していれば1都市が壊滅するところだった」としている。

地元メディアによると、同博士は2月27日、200万キロ以上離れた宇宙空間に時速3万1000キロもの速度で地球に向かって来る未知の天体を発見し、軌道を計算したところ、太陽の周りを1年半かけて公転する小惑星だった。この小惑星は3日午前0時40分(日本時間2日午後10時40分)に地球に最も近づき、その距離は、月との距離(約38万キロ)の6分の1弱に当たる約6万キロだった。

この小惑星の大きさは、1908年にロシア・シベリアに落ち、2000平方キロの森を焼き尽くしたものに匹敵したという。

地球への再接近は100年以上先になる見込み。

国立天文台の入江誠・広報普及員の話 「小惑星と地球との距離が6万キロ・メートルというのは、宇宙の距離としてはものすごく近い。小惑星がここまで地球に接近するのは珍しいことだ。地球に衝突せずに通過してよかった」

(2009年3月6日12時29分 読売新聞)

*****以下は関連記事(New Scientist 誌)

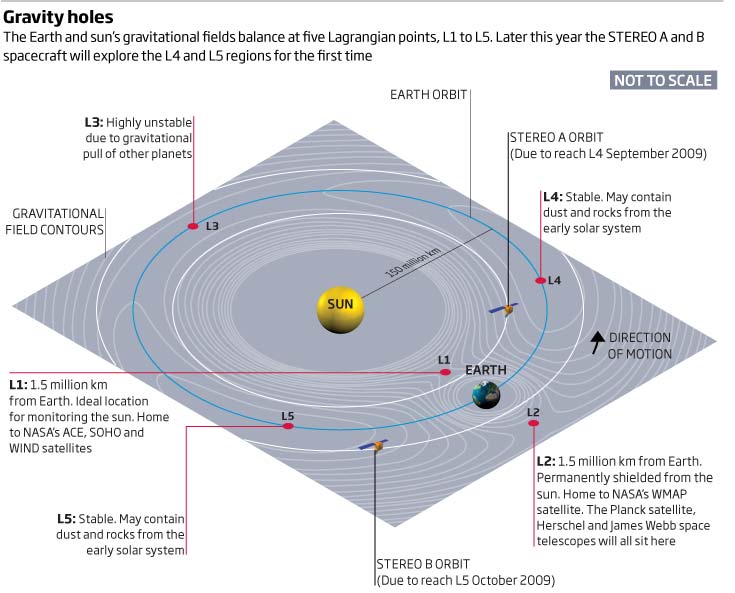

太陽系内部に太陽と地球の重力がちょうどバランスし合って、一見無重力状態の空間がある(図参照)。これを「重力ホール」と呼ぶことにする。其の重力ホールに地球を標的にする宇宙の物体(主として小惑星)を誘導しようという筋書き。そのために、先ずは其の重力ホールの調査が始まる。

(本文は長いので、最初の3分の1のみ、興味ある方々は、下記URLを訪ねられたい)

http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg20126962.000-do-gravity-holes-harbour-planetary-assassins.html?DCMP=NLC-nletter&nsref=mg20126962.000

Do gravity holes harbour planetary assassins?

重力ホールは宇宙の刺客をうまく繋留できるだろうか?

THEY are the places gravity forgot. Vast regions of space, millions of kilometres across, in which celestial forces conspire to cancel out gravity and so trap anything that falls into them. They sit in the Earth's orbit, one marching ahead of our planet, the other trailing along behind. Astronomers call them Lagrangian points, or L4 and L5 for short. The best way to think of them, though, is as celestial flypaper.

In the 4.5 billion years since the formation of the solar system, everything from dust clouds to asteroids and hidden planets may have accumulated there. Some have even speculated that alien spacecraft are watching us from the Lagrangian points, looking for signs of intelligence.

Putting little green men to one side for the moment, even the presence of plain old space rocks would be enough to keep most people happy. "I think you certainly might find a whole population of objects at L4 and L5," says astrophysicist Richard Gott of Princeton University.

After nearly a century of speculation, we are on the verge of finding out what they are hiding once and for all. Later this year, two spacecraft that spend their lives studying the sun will begin their slow journeys through L4 and L5.

Space scientists plan to use instruments on board NASA's STEREO probes A and B to search for celestial objects becalmed at the Lagrangian points. What they find could hugely enhance our view of how the solar system formed, tell us more about the colossal impact that formed the moon, and warn us if another major collision is on the cards.

The Lagrangian points were first discovered in 1772 by the mathematician Joseph-Louis Lagrange. He calculated that the Earth's gravitational field neutralises the gravitational pull of the sun at five regions in space, making them the only places near our planet where an object is truly weightless.

Of the five Lagrangian points, L4 and L5 are the most intriguing. They are the only ones that are stable: while a satellite parked at L1 or L2 will wander off after a few months unless it is nudged back into place, any object at L4 or L5 will stay put due to a complex web of forces. Lying 150 million kilometres away, along the line of Earth's orbit, L4 circles the sun 60 degrees in front of our planet while L5 lies at the same angle behind (see diagram).

Evidence for such gravitational potholes appears around other planets too. In 1906, Max Wolf discovered an asteroid outside of the main belt between Mars and Jupiter, and recognised that it was sitting at Jupiter's L4 point. Wolf named it Achilles, and so began the tradition of naming these asteroids after characters from the Trojan wars.

The realisation that Achilles would be trapped in its place and forced to orbit with Jupiter, never getting much closer or further away, started a flurry of telescopic searches for more examples. There are now more than 1000 asteroids known to reside at each of Jupiter's L4 and L5 points.

Searches for "Trojan" asteroids around other planets have met with mixed results. Saturn seemingly has none, and only in the last decade have Trojans been found at Neptune. Naturally, astronomers have often wondered about asteroids at Earth's L4 and L5 points.

Fly-through zones

The trouble is that our L4 and L5 points are not easy to see from the ground. They appear to lie close to the sun, so by the time night falls, the trailing L5 region is low in the sky and setting fast. On the other side of the sky, the preceding L4 point rises in darkness but the dawn is hot on its heels.

That didn't prevent Paul Weigert at the University of Western Ontario in Canada and his colleagues from conducting a number of searches in the 1990s with the Canada-France-Hawaii telescope on Mauna Kea, Hawaii. It was a tough job because L4 and L5 appear wider in the sky than the full moon so a large number of observations would be needed to search them thoroughly. Alas, Weigert and colleagues came up empty-handed as their search wasn't detailed enough.

More recently, automated asteroid searches, such as the Lincoln Near Earth Asteroid Research project, have begun to creep closer to the Lagrangian points in their nightly robotic scans of the sky, but at this stage no Lagrangian asteroids have been identified. "The field has languished because we are all waiting for somebody to see something," says Weigert.

NASA's STEREO spacecraft could change everything - even though they were never designed to look for asteroids. Launched in 2006, one of the twin STEREO probes was placed ahead of Earth, the other behind. Tracing Earth's orbit, STEREO A gradually outpaces the Earth while its sister ship, STEREO B, trails ever further behind. From these two vantage points, the spacecraft monitor the region of space directly between the Earth and the sun, looking for solar storms that can wreak havoc with electrical equipment on satellites and on Earth.

|

|

|

|

投稿コメント全ログ コメント即時配信 スレ建て依頼 削除コメント確認方法

|

|

題名には必ず「阿修羅さんへ」と記述してください。

題名には必ず「阿修羅さんへ」と記述してください。

掲示板,MLを含むこのサイトすべての

一切の引用、転載、リンクを許可いたします。確認メールは不要です。

引用元リンクを表示してください。

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|