|

|

(回答先: NYT:ブッシュのイラクでの死傷者激増に関する発言が問題化してるらしい。 投稿者 木村愛二 日時 2003 年 11 月 06 日 00:29:29)

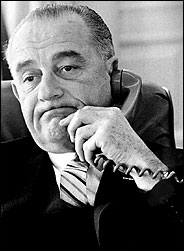

早速、はいこれ。ベトナム戦死者でつまづき、意気消沈するジョンソン大統領写真つき。

Associated Press

President Lyndon B. Johnson, shown here on Jan. 10, 1964, saw his presidency consumed by American casualties in Vietnam.

【AP】

リンドン B.ジョンソン米国大統領は、1964年1月10日、彼の大統領職がベトナムでの米兵等戦死者により風前のともし火となったことを悟った。

Issue for Bush: How to Speak of Casualties?

By ELISABETH BUMILLER

Published: November 5, 2003

ASHINGTON, Nov. 4 ? When the Chinook helicopter was shot down on Sunday in Iraq, killing 15 Americans, President Bush let his defense secretary do the talking and stayed out of sight at his ranch. The president has not attended the funeral of any American soldiers killed in action, White House officials say. And with violence in Baghdad dominating the headlines this week, he has used his public appearances to focus on the health of the economy and the wildfires in California.

But after some of the deadliest attacks yet on American forces, the White House is struggling with the political consequences for a president who has said little publicly about the mounting casualties of the occupation.

The quandary for Mr. Bush, administration officials say, is in finding a balance: expressing sympathy for fallen soldiers without drawing more attention to the casualties by commenting daily on every new death.

White House officials say their strategy, for now, is to avoid having the president mention some deaths but not others, and so avoid inequity. (Mr. Bush does send a personal letter to the family of every soldier killed in action and has met privately with relatives at military bases.)

"He never wants to elevate or diminish one sacrifice made over another," said Dan Bartlett, the White House communications director.

Or, as another White House official put it: "If you're the brother or mother of a soldier who was killed on Saturday, and nothing was said, and then the president says something on Sunday? Unless the president starts saying it for all of them, he can't do it."

Republicans also acknowledge that White House officials, mindful of history, do not want Mr. Bush to become hostage to daily body counts, much as President Lyndon B. Johnson was during the Vietnam War. Concern about being consumed by the headlines, administration officials say, is another reason the president did not specifically address the downed Chinook on Sunday.

"If a helicopter were hit an hour later, after he came out and spoke, should he come out again?" Mr. Bartlett said. The public "wants the commander in chief to have proper perspective and keep his eye on the big picture and the ball. At the same time, they want their president to understand the hardship and sacrifice that many Americans are enduring at a time of war. And we believe he's striking that balance."

So Mr. Bush is continuing to refer as broadly as possible to the sacrifice of all, as when reporters asked him in California on Tuesday to comment directly on the attack against the helicopter.

"I am saddened any time that there's a loss of life," replied Mr. Bush, who added that the soldiers killed had died "for a cause greater than themselves," the campaign against terrorism.

Some Republicans say they are concerned that the White House strategy leaves the president open to accusations from Democrats that he is isolated from the real pain of war.

"I have to say, I think we have to note tragedies of this magnitude," the Senate Democratic leader, Tom Daschle of South Dakota, told reporters on Tuesday, referring to Sunday's attack. "I think it needs to be expressed over and over by the president, and I think all deference ought to be given those dead and wounded who return home."

David R. Gergen, who worked in the Nixon, Ford, Reagan and Clinton White Houses, called the subject a "tender" one. He said he understood the White House concern about allowing Mr. Bush to be drawn into every death in Iraq, and recalled past presidents who were advised by their staffs not to meet with the families of American hostages.

"Even so," Mr. Gergen said, "we're now encountering deaths at rates we haven't seen since Vietnam, and I think it's important for the country to hear from the president at times like these, and for families to know. I think the weight is on the side of clear expression."

Others say the White House strategy can add to the anguish of families who have lost loved ones in Iraq. Thomas Wilson, an uncle of Staff Sgt. Joe N. Wilson, 30, of Crystal Springs, Miss., who was killed in the helicopter attack, went so far as to tell a reporter on Monday that Mr. Bush and members of his family needed to experience Iraq for themselves. "Then he'll realize what's going on," Mr. Wilson said. "As long as they ain't over there, he don't care."

Mr. Bartlett would not discuss how much concern comments like Mr. Wilson's had created at the White House.

"The president writes a letter to every family of a fallen soldier and meets privately with families of soldiers at military bases," Mr. Bartlett said. "He grieves with them, he understands. I'm not going to judge anybody's comments made in such a difficult period. People say a lot of things."

Some close to the president say another reason he has not expressed more public sympathy for individual soldiers killed in Iraq is his determination to let families have their privacy. He was offended, his friends say, by what he saw at times as President Bill Clinton's exploitation of private grief for political gain.

Like other presidents, Mr. Clinton appeared at some military funerals. In October 2000, he attended a memorial service in Norfolk, Va., for the 17 sailors killed in the bombing of the guided-missile destroyer Cole. In 1983, President Ronald Reagan attended a memorial service at Camp Lejeune, N.C., for 241 marines killed in Beirut. President Jimmy Carter attended ceremonies for troops killed in the failed hostage-rescue mission in Iran.

Marlin Fitzwater, who was White House press secretary to President Bush's father, recalled that the elder Mr. Bush "went to a number of memorial ceremonies" where he met with families of troops killed in action in the Persian Gulf war of 1991.

At the time of that war, the Pentagon barred media coverage of coffins arriving at Dover Air Force Base in Delaware. The ban was relaxed during the Clinton administration, but then reinforced by the second Bush administration in the run-up to the current hostilities in Iraq.

|

|

|

|

|

|

題名には必ず「阿修羅さんへ」と記述してください。

題名には必ず「阿修羅さんへ」と記述してください。

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|